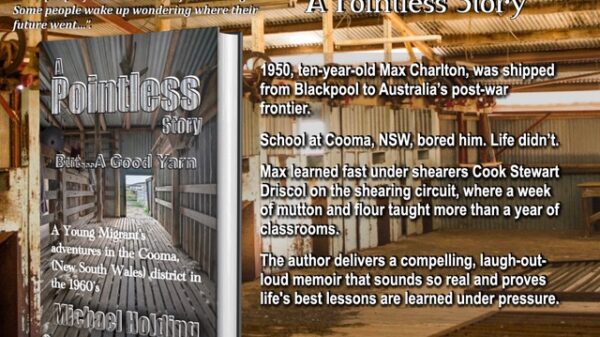

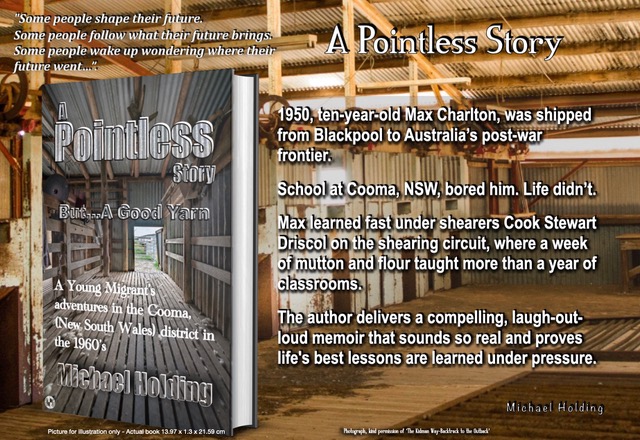

The role of a shearer’s cook during the 1950s and 1960s involved far more than preparing meals; it demanded an array of skills that combined culinary expertise with practical knowledge of butchery and logistics. As described in Michael Holding’s book, “A Pointless Story,” the shearer’s cook served as the backbone of the shearing team, often working tirelessly to ensure that the crew was well-fed and ready for the demanding physical labor ahead.

The Multifaceted Responsibilities of a Shearer’s Cook

In the demanding environment of sheep shearing, a cook was responsible for every aspect of food preparation. This meant acting as a slaughterman and butcher, where the cook needed to skillfully handle livestock. Sheep—and sometimes cattle—had to be killed and processed efficiently. This required not only knowledge of how to carry out these tasks but also the ability to do so with speed and precision.

Beyond butchery, the cook also had to master baking and cooking. Each day began early, with a cook preparing hot bread, scones, and hearty meals to fuel the shearers. Working with wood-fired ovens required an understanding of how to maintain consistent heat, especially in unpredictable weather conditions.

The sheer volume of food prepared was significant. A cook typically managed three full meals a day for up to twenty men, plus mid-morning and afternoon snacks. This included planning menus, managing supplies, and ensuring nothing spoiled in the summer heat. The hours were grueling, starting at around 4:00 a.m. and often stretching well into the evening.

A top cook could earn between £30 to £40 per week, comparable to the best shearers. Unlike the shearers, whose pay depended on the weather and work availability, the cook’s income remained stable. Their payment structure was unique, typically involving a percentage of each shearer’s wages, which reinforced the cook’s integral role within the team.

The Daily Grind: A Snapshot of Life in the Kitchen

Michael Holding’s narrative provides a vivid depiction of a typical day for a shearer’s cook. The morning routine began with the sound of Stew, a seasoned cook, rousing the team. The air was filled with the aroma of sizzling sausages and bacon as he fired up multiple cast-iron frypans, preparing a breakfast fit for hard workers.

By 5:30 a.m., the shearers arrived, often silent and half-awake as they consumed their meals at an astonishing pace. The aftermath left a kitchen in disarray, with piles of dishes and greasy pans awaiting cleaning. Stew and his assistant faced a relentless cycle of cooking and cleaning, with little time to rest.

The day continued with sandwich preparations for the crew’s breaks, often interrupted by the urgent need to manage livestock, depending on the farmer’s schedule. The cook’s efficiency was vital, as they navigated the demands of the job while maintaining high food quality.

As the evening approached, the kitchen became a hub of activity once more. The shearers returned, full of energy and camaraderie, and the cook prepared to serve a hearty dinner. After another round of washing dishes, the day would finally wind down around 8:30 p.m., with both the cook and his assistant utterly exhausted.

The cook’s role, as Holding illustrates, was not merely about cooking. It involved a blend of skills that included butchery, baking, and a keen understanding of human psychology. A good cook earned respect through his ability to keep the team fed, happy, and productive. The reputation of a shearer’s cook could make or break a shearing operation, highlighting their importance in this rugged Australian lifestyle.

In conclusion, the life of a shearer’s cook was a testament to hard work, skill, and resilience. Despite the demanding nature of the job, the cook played a critical role in ensuring that the team could perform at their best, earning a unique place in the history of Australian shearing culture.