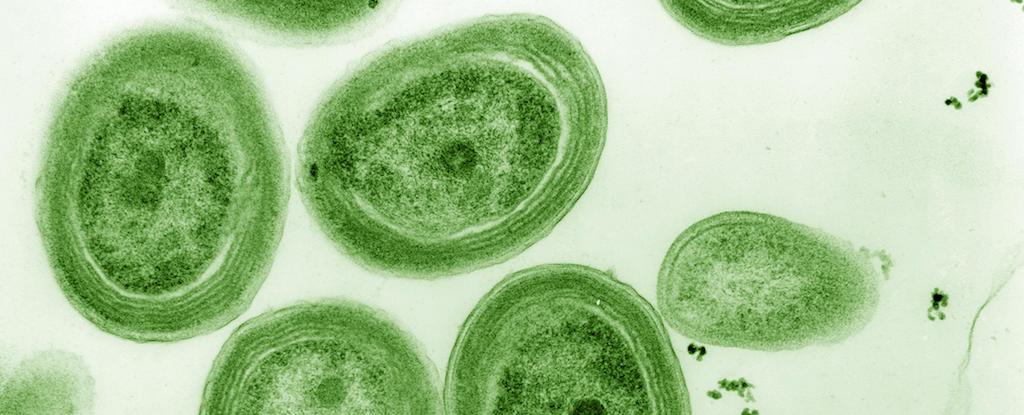

Recent research raises alarming concerns about the survival of Prochlorococcus, a microbe that plays a crucial role in Earth’s oxygen production. Found predominantly in tropical and subtropical waters, this organism contributes nearly a third of the planet’s oxygen. However, a new study led by oceanographer François Ribalet from the University of Washington indicates that rising ocean temperatures may pose a significant threat to its viability.

Prochlorococcus thrives in over 75 percent of sunlit surface waters, particularly in warm, nutrient-poor environments. Ribalet describes these areas: “Offshore in the tropics, the water is this bright, beautiful blue because there’s very little in it, aside from Prochlorococcus.” While some scientists previously believed that increased temperatures would benefit this microbe, the findings suggest otherwise.

The study reveals that Prochlorococcus has an ideal temperature range of 19 to 28 degrees Celsius (66 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit). Unfortunately, many tropical waters are expected to exceed this upper limit within the next 75 years due to climate change. Ribalet states, “In the warmest regions, they aren’t doing that well, which means there is going to be less carbon – less food – for the rest of the marine food web.”

The research team collected data from wild Prochlorococcus over a span of 13 years, conducting 90 research voyages that analyzed 800 billion microbial cells. Utilizing a custom-designed flow cytometer, the researchers measured cell division rates and found that these rates plummeted in water exceeding 30 degrees Celsius. Ribalet notes, “Their burnout temperature is much lower than we thought it was.”

Tropical seas, typically nutrient-poor, limit the upward cycling of essential nutrients. Prochlorococcus has adapted to these conditions with a streamlined genome, which may reduce its resilience to changes in temperature. Meanwhile, another cyanobacteria group, Synechococcus, could potentially take advantage of Prochlorococcus’s decline. Although Synechococcus can tolerate warmer waters, its higher nutrient requirements might disrupt existing marine ecosystems.

The study predicts that by the end of this century, Prochlorococcus productivity could decrease by 17 percent under moderate warming scenarios, and by as much as 51 percent with severe warming. Globally, this translates to a potential drop of 10 percent from moderate warming and 37 percent from more extreme conditions. Ribalet emphasizes, “Their geographic range is going to expand toward the poles, to the north and south.”

Despite these findings, the study has its limitations, including the possibility of overlooking rare heat-resistant strains. Ribalet acknowledges, “If new evidence of heat-tolerant strains emerges, we’d welcome that discovery. It would offer hope for these critical organisms.” The research is published in Nature Microbiology.

This study underscores the urgent need for ongoing investigation into the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems, as the health of Prochlorococcus is vital for maintaining the planet’s oxygen levels and supporting diverse marine life.