URGENT UPDATE: New research has uncovered that wastewater from aircraft toilets could be a vital tool in the fight against antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) superbugs, a looming threat projected to kill more people than cancer by 2050. Scientists from Australia’s national science agency CSIRO and partners from Xiamen University, the University of South Australia, and Michigan Technological University conducted a pivotal study analyzing lavatory wastewater from 44 international flights landing in Australia.

This groundbreaking study detected nine high-priority pathogens and superbugs, some resistant to multiple drugs and typically acquired in hospitals. The findings, published in Microbiology Spectrum, indicate that these pathogens could serve as an early warning system for the global spread of AMR.

The researchers employed advanced molecular techniques to analyze the superbugs’ genetic signatures and antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) profiles. Alarmingly, five of the nine identified superbugs were present in all 44 flight samples, and a gene linked to resistance against last-resort antibiotics was found on 17 flights. Notably, this gene was absent in urban wastewater samples from Australia during the same timeframe, indicating its likely introduction through international travel.

According to Dr. Warish Ahmed, a principal research scientist at CSIRO and senior author of the study, “Aircraft wastewater captures microbial signatures from passengers across different continents, offering a non-invasive, cost-effective way to monitor threats like AMR.” This innovative approach could transform how we detect and address emerging public health risks.

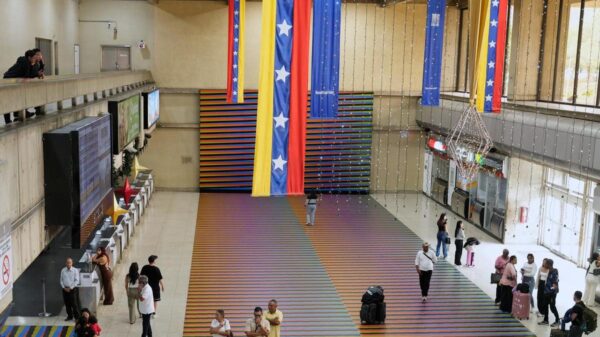

The study’s co-author, Professor Nicholas Ashbolt from the Future Industries Institute, highlighted significant geographic variations in the findings, stating, “Flights from Asia, particularly India, showed higher concentrations of antibiotic resistance genes compared to flights from Europe and the UK.” Of the 44 flights analyzed, 18 were from India, 14 from the UK, and others included flights from Germany, France, the UAE, Türkiye, South Africa, Japan, and Indonesia.

Lead author Dr. Yawen Liu, visiting scientist at CSIRO from Xiamen University, emphasized that these disparities may reflect differences in antibiotic usage, water sanitation, population density, and public health policies across regions. The study also assessed whether disinfectants used in aircraft toilets degrade genetic material, finding that nucleic acids remained stable for up to 24 hours, even in the presence of strong disinfectants.

“International travel is one of the major drivers of AMR spread,” Dr. Liu stated. “By monitoring aircraft wastewater, we can potentially detect and track antibiotic resistance genes before they become established in local environments.”

With infectious diseases like tuberculosis, influenza, and SARS-CoV-2 known to spread via air travel, the implications of this research are profound. The samples were collected during COVID-19 pandemic repatriation flights, which might have affected passenger demographics, but the authors believe this monitoring strategy can be adapted for routine international travel.

The urgency of the findings cannot be overstated. With AMR expected to cause over 39 million deaths globally by 2050, the call for innovative surveillance tools is pressing. “Aircraft wastewater monitoring could complement existing public health systems, providing early warnings of emerging superbug threats,” Professor Ashbolt remarked.

“This is a proof-of-concept with real-world potential,” Dr. Ahmed concluded. “We now have the tools to turn aircraft toilets into an early-warning disease system to better manage public health.”

As the world grapples with the silent pandemic of antimicrobial resistance, this new research serves as a crucial step toward safeguarding global health. The implications for international travel, public health policies, and disease management are immense, making this a critical development to watch closely.