Concerns about Canada’s political landscape mirror those expressed about the United States, with some observers fearing a rise in political polarization. New research offers a different perspective, suggesting that while partisan animosity exists, Canada is not as deeply divided as its southern neighbor. This study indicates that Canadians exhibit moderate levels of affective polarization and low to moderate political sectarianism.

Affective polarization is defined as the emotional gap between individuals who share political beliefs and those who do not. Unlike policy disagreements, it focuses on feelings of warmth or hostility towards opposing groups. In the United States, this phenomenon has escalated dramatically, leading to a breakdown in trust and cooperation among citizens.

To understand the state of political animosity in Canada, researchers from the Canadian Hub for Applied and Social Research (CHASR) at the University of Saskatchewan conducted a survey of 2,503 Canadians in the summer of 2024. This survey is notable for being the first to measure political sectarianism in a nationally representative sample within Canada, providing unique insights into the country’s political dynamics.

Participants were asked to identify their political ideology on a scale from zero (extremely left-wing) to ten (extremely right-wing), with moderates selecting five. The respondents also rated their feelings towards left-wing and right-wing Canadians using a feeling thermometer, which gauges emotional warmth on a scale from 0 to 100.

The findings reveal a complex landscape. Canadians demonstrate moderate affective polarization, with individuals showing greater warmth for their own political group compared to those on the opposite side. Left-wing Canadians reported a stronger dislike for right-wing individuals than vice versa. This discrepancy aligns with patterns observed in other countries, potentially stemming from differing perceptions of social and moral threats.

Understanding Political Sectarianism in Canada

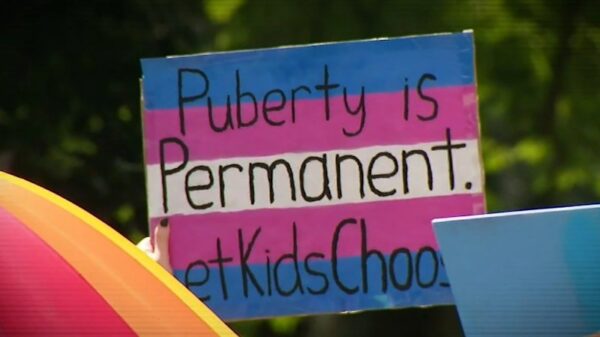

Political sectarianism, which describes the moral identification with one political group against another, reflects a deeper level of animosity. The study identified three dimensions of this phenomenon: aversion, or negative feelings toward the opposing side; othering, or viewing the other side as incomprehensible; and moralization, or believing the opposing group is immoral.

In Canada, the research indicates low to moderate levels of political sectarianism. While left-wing Canadians exhibit moderate aversion, few respondents regard the opposing political side as immoral. Both political factions display moderate tendencies toward othering, suggesting that while divisions exist, they have not escalated to the level of hatred or dehumanization observed elsewhere.

Who’s Most Affected by Polarization?

The data suggest that left-wing individuals are generally more polarized than their right-wing counterparts. Supporters of the New Democratic Party (NDP), the Conservative Party of Canada, and the People’s Party demonstrate the highest levels of polarization. Approximately one-fifth of Canadians identify as politically unaffiliated, which could account for the more polarized nature of the two right-wing parties compared to the Liberal Party.

Demographic factors also play a role in polarization levels. Older Canadians tend to exhibit higher polarization than younger individuals, while residents of Atlantic Canada show less polarization compared to those in Alberta. The study found no significant differences in polarization across gender, race, or education level.

The implications of these findings are significant. A functioning democracy relies on citizens’ ability to respect differing viewpoints across various social and political divides. Partisan animosity can undermine this tolerance, eroding trust in institutions and fellow citizens. The fact that Canada remains moderately polarized, with low to moderate political sectarianism, offers a glimmer of hope.

Yet, there are notable areas of concern. The left’s greater aversion to the right and the moderate polarization among supporters of the NDP, Conservative Party, and People’s Party could deepen over time. Influences such as social media algorithms, partisan media, and political leaders who prioritize outrage over understanding might exacerbate these divides.

Looking ahead, Canada’s political culture currently shields it from the extreme polarization evident in the United States. Canadians continue to engage with mainstream media and credible news sources, providing a buffer against the pressures that have intensified polarization elsewhere. Nevertheless, the hostile climate in Parliament and widening gaps in social attitudes between the political left and right could threaten this stability.

In conclusion, the current polarization narrative in Canada is one of caution rather than crisis. While political differences are genuine, they have not yet resulted in significant divisions. Protecting this advantage is crucial as the country navigates its political future. The research was conducted by Emily Huddart and Tony Silva, with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.