Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that impacts brain function, influencing behaviour, communication, and social interaction. A growing body of research indicates that individuals on the autism spectrum often exhibit distinct differences in their walking patterns, known as “gait.” Notably, these variations are now recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a supporting diagnostic feature of autism.

Recognizing Gait Variations

Among the most prominent gait differences observed in autistic individuals are toe-walking, walking on the balls of the feet, in-toeing (where one or both feet turn inward), and out-toeing (where one or both feet turn outward). Research spanning over three decades has illuminated additional subtler differences, including slower walking speeds, wider steps, and prolonged time spent in the stance phase—when the foot is in contact with the ground.

Autistic individuals often display significant variability in their stride length, walking speed, and overall gait patterns. These differences frequently co-occur with other motor challenges, such as balance issues, coordination difficulties, and postural stability. Consequently, many autistic individuals may require additional support for these related motor skills.

Causes of Gait Differences

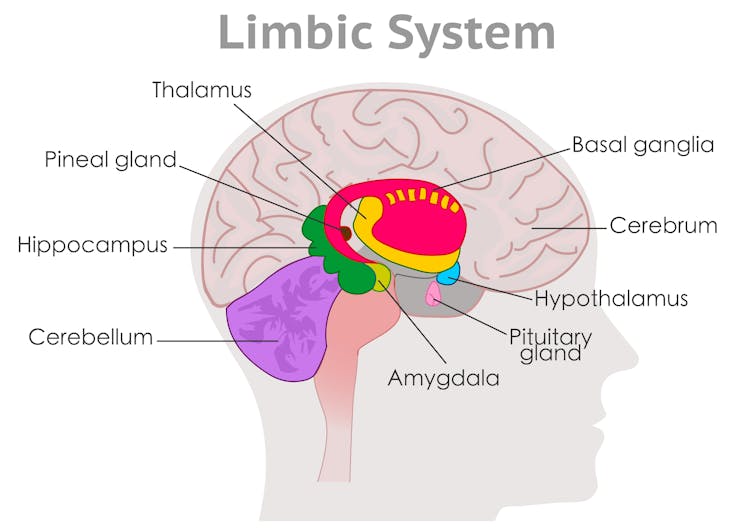

The underlying causes of these gait variations are primarily linked to differences in brain development, particularly within the basal ganglia and cerebellum. The basal ganglia play a crucial role in sequencing movements and managing postural shifts, ensuring that walking appears smooth and automatic. The cerebellum utilizes visual and proprioceptive information to fine-tune movements, maintaining stability and coordination.

Research indicates that developmental differences in these brain regions influence their structure, function, and connectivity with other brain areas. While some earlier theories proposed that gait differences stemmed from delayed development, current evidence suggests that these variations persist throughout a person’s life, often becoming more pronounced with age.

Furthermore, an individual’s gait is also influenced by their overall motor, language, and cognitive abilities. Those with more complex support needs may experience more noticeable gait and motor differences, often accompanied by language and cognitive challenges. Notably, motor dysregulation can signal sensory or cognitive overload, serving as an indicator that an individual may benefit from additional support or a break.

Management and Support Strategies

Not all gait differences necessitate treatment. Clinicians typically adopt an individualized, goal-oriented approach when assessing the need for support. For instance, subtle gait variations that do not hinder participation in daily activities may not require intervention. In contrast, if gait differences lead to increased risk of falls, difficulties in engaging in preferred physical activities, or physical discomfort in areas such as the feet or back, then support becomes essential.

Children may particularly benefit from assistance in developing motor skills. This support does not have to be confined to clinical settings. Programs that incorporate movement opportunities within school environments can help autistic children enhance their motor skills alongside their peers. For example, the Joy of Moving Program in Australia promotes physical activity in classrooms, encouraging students to engage actively.

Community-based interventions, such as sports or dance, have also shown promise in improving movement abilities among autistic children. These models empower children to embrace their unique movement styles rather than viewing them as problems to be solved.

Future Directions

Despite advancements in understanding gait differences among autistic individuals, researchers and clinicians continue to seek a deeper insight into the causes and timing of individual variability. There is also ongoing exploration into the best strategies for supporting diverse movement styles, particularly as children grow and develop.

Encouragingly, evidence suggests that physical activity can enhance social skills and behavioral regulation in preschool-aged children with autism. As a result, various states and territories are shifting towards more community-based foundational supports for autistic children and their peers. This development aligns with ongoing efforts to create inclusive environments beyond the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The insights shared in this article draw upon contributions from various experts in the field, including the late Emeritus Professor John Bradshaw, and are supported by funding from organizations such as the Moose Happy Kids Foundation, Ferrero Australia, and the Australian Football League. As research continues, the hope is to provide even better support for the diverse needs of autistic individuals and to foster environments where they can thrive.