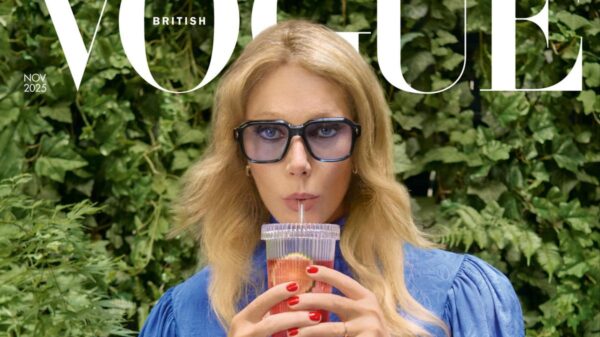

Border officials possess far more information than travelers might expect regarding their identities and travel histories. A recent incident involving Australian traveler Pauline Ryan illustrates how a seemingly routine entry process can lead to unexpected complications. Ryan, a semi-retired psychologist, faced denial of entry into the United States after a ten-month journey through South and Central America, bringing to light the complexities of passport control.

On July 19, 2023, Ryan and her partner arrived at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) at 16:20. After a lengthy wait in the immigration queue, Ryan was informed by a friendly immigration officer that her partner could proceed but she was being detained. The abruptness of the situation left her in disbelief.

Once taken to a secondary holding area, Ryan described an intrusive process that included a thorough search, fingerprinting, and the confiscation of her belongings. She was informed that her Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) visa was invalid due to a trip she had taken to Iran in 2013. Despite having declared this visit during her visa application and receiving approval, border officials stated that her previous travel to a country deemed a sponsor of terrorism rendered her ineligible for entry.

Ryan’s ordeal continued as she was not allowed to communicate with her partner or use her phone. Instead, she was placed on an expensive last-minute flight to Singapore, described by her as a “walk of shame” through the airport, escorted by security personnel. Upon arrival in Singapore, she faced further questioning and was denied entry again, ultimately forcing her to return to Australia.

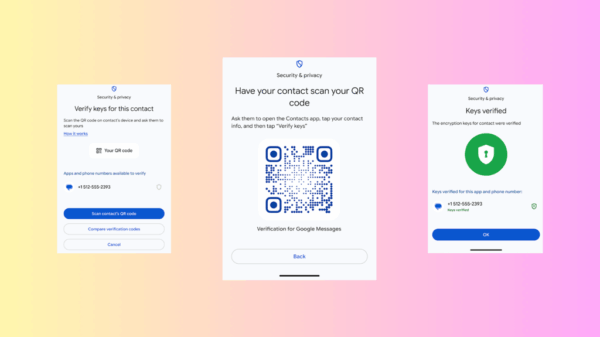

The situation raises critical questions about what information border officials access when scanning a passport, particularly in light of the extensive data shared by airlines. Dr. Nina Toft Djanegara, a Technology, Law and Policy Fellow at the University of California, explained that the embedded chip in e-passports contains personal details such as biometric data, which can be verified in real-time.

When a flight is booked, a Passenger Name Record (PNR) is created, linking critical travel information. Dr. Toft Djanegara elaborated that airlines send this data to the destination country up to 72 hours before departure, allowing border authorities to build a comprehensive profile of a traveler’s movements. This includes details such as name, address, itinerary, meal preferences, and payment methods.

In addition to passport and booking data, border officials also have access to security databases from organizations like Interpol, as well as national watch lists and criminal records. Dr. Toft Djanegara noted that any flags on record could impact decisions made at the border, indicating that previous visa denials from other countries can follow a traveler and influence their entry.

As travel resumes, Australians returning from overseas may encounter similar scrutiny from border officials. The advanced systems used by companies like SITA facilitate the sharing of passenger information with governments, allowing for tracking of individual movements as well as identities. While this enhances security, it raises concerns about privacy and the potential for profiling or erroneous assessments.

Ryan’s experience highlights that possessing a valid visa does not guarantee entry into the United States or any country, as border officers wield considerable discretion in their evaluations. Dr. Toft Djanegara emphasized that the legal environment in which border control officers operate is complex, and their decisions can be influenced by factors beyond mere documentation.

In a related note, the cost of obtaining an Australian passport has raised eyebrows, with the price currently around AUD 412 for a ten-year document. This places Australia among the most expensive passport issuers globally, alongside the United Kingdom and the United States. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), the price reflects the advanced security features and the passport’s global reputation, which offers Australians visa-free access to over 180 countries.

Despite these advantages, Australia’s ranking has slipped from sixth to seventh in the Henley Passport Index, which measures passport strength based on visa-free access. Currently, Australia shares this position with Malta and Poland, while Singapore, Japan, and South Korea lead the index.

As travel resumes and international borders open, understanding the complexities of passport control and the information that accompanies it becomes increasingly important for all travelers.