Wheat growers in Kentucky are gaining critical tools to manage crop diseases more effectively. Researchers at the University of Kentucky are developing practical solutions that allow farmers to assess risks earlier and make informed decisions regarding fungicide applications. This initiative is part of the National Predictive Modeling Tool Initiative (NPMTI), a collaborative effort led by the USDA Agricultural Research Service focused on improving disease forecasting.

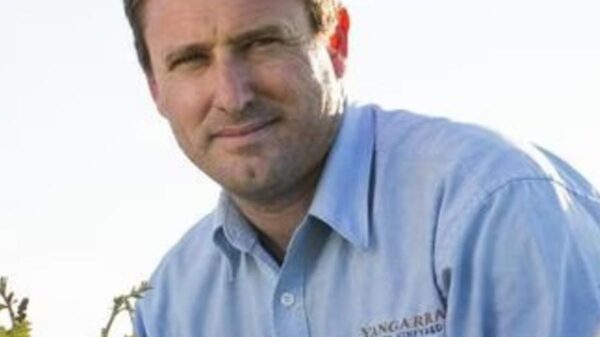

The project targets soft red winter wheat, the predominant variety cultivated in Kentucky. According to Carl Bradley, an extension professor in the Department of Plant Pathology, the primary objective is to provide farmers with precise local risk information for leaf diseases. This information enables them to determine when and whether to apply fungicides effectively.

Predicting Leaf Diseases

Leaf diseases can escalate rapidly under favorable conditions, making timely intervention crucial. The research team is validating a stripe rust risk model developed by Erick De Wolf at Kansas State University. The Kentucky team is applying this model to local conditions by monitoring test plots statewide for disease prevalence and weather patterns. When the model indicates a higher risk, fungicides are applied, and the outcomes are compared to unsprayed plots to evaluate the model’s accuracy and economic viability.

In addition to modeling, researchers implement airborne pathogen monitoring to enhance early detection. Each spring, spore traps are placed in various wheat fields across Kentucky. These traps collect samples weekly, which are sent to laboratories for DNA extraction and analysis. This data helps quantify key pathogens that threaten wheat crops. By correlating these numbers with on-site weather data and field observations, the team can better assess infection likelihood and refine their predictive models.

Addressing Fusarium Head Blight

While leaf diseases pose significant challenges, Kentucky wheat growers face a persistent threat from Fusarium head blight, commonly known as head scab. This fungal infection attacks wheat heads during flowering, producing a toxin called deoxynivalenol (DON), also referred to as vomitoxin. Grain contaminated with DON poses risks to both human and livestock health, leading to price reductions or even rejections at grain elevators when contamination exceeds regulatory limits.

Bradley emphasizes a two-part strategy to combat this issue: planting resistant wheat varieties and timing fungicide applications effectively. “Resistant varieties combined with well-timed fungicide applications can significantly mitigate DON levels in many growing seasons,” he noted.

The collaboration also extends to researchers across the university. Dave Van Sanford, a wheat breeder in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, is developing varieties that offer enhanced resistance while remaining suitable for Kentucky’s agronomic conditions. Meanwhile, Lisa Vaillancourt, a plant pathologist, investigates the biology of the head scab pathogen to identify potential management strategies.

Kentucky’s involvement in NPMTI emphasizes the importance of data quality. The research team is creating comprehensive datasets from both past epidemics and current growing seasons to refine predictive models nationwide. Insights gained from commercial fields will validate whether effective tools in controlled plots translate to real-world agricultural settings with diverse soils and farming practices.

As this initiative progresses, partnerships with organizations such as the National Agricultural Genotyping Center will facilitate DNA analyses, while national laboratories explore how to deliver risk assessment tools in user-friendly formats.

Bradley concludes, “This initiative is essential for maintaining the profitability and marketability of Kentucky wheat. With timely risk information tailored to their fields and varieties, growers can make informed decisions that protect their crops and ultimately feed people and livestock.”