The future of Western Australia’s ambitious Wheatbelt Secondary Freight Network (WSFN) is uncertain as funding is set to expire, leaving thousands of kilometres of crucial road upgrades unfinished. Since its inception in 2019, this extensive program has involved collaboration among 42 local governments to enhance safety and efficiency on rural roads. However, as the deadline approaches, calls for renewed Federal and State government support are growing louder.

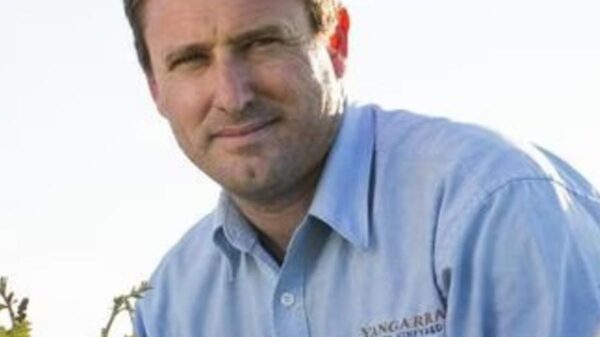

John Nuttall, program director of the WSFN, highlighted the significance of the project, stating, “The WSFN is a 4,400-kilometre freight route that connects the entire Wheatbelt region. Significant improvements have already been made across several hundreds of kilometres, but we need more funding to continue.” The program is set to conclude in 2026, and without additional resources, many improvements may be at risk of reversal.

The WSFN is governed by a steering committee that includes representatives from regional road groups, Main Roads WA, the WA Local Government Association, the Wheatbelt Development Commission, and Regional Development Australia. The initiative was born from a need to facilitate more efficient grain transport for farmers, particularly in areas lacking rail access. Over time, it has transformed into a comprehensive strategy for establishing safer and more effective freight corridors.

These routes consist of local government-managed roads that provide vital connections to State and national highways, essential for accommodating heavy vehicles and supporting not only freight supply chains but also tourism within the region. In 2024-25, the Wheatbelt is projected to generate $9.1 billion in gross regional product, with agricultural output alone exceeding $5.3 billion, representing over a third of Western Australia’s total.

Despite these significant contributions, many roads in the Wheatbelt are not built to accommodate the increasing size and weight of vehicles necessary for competition. Nuttall emphasized the importance of a robust supply chain that includes road, rail, sea, and air transport. He stated that a holistic approach is vital for improving productivity and ensuring access to key agricultural commodities for both domestic and international markets.

“We have a list of routes that are prioritised by road condition and traffic,” Nuttall explained. “We work our way down the priority list, and funding is provided over a certain number of years.” Each of the 42 shires is organized into eight sub-regional road groups, with elected members representing them on both the steering and technical committees. The steering committee’s role is to offer strategic guidance, while the technical committee focuses on the practical aspects of the program.

Local expertise is crucial in determining the secondary freight route’s layout, allowing for flexibility as conditions change. “If, for example, a grain receival site closed and another opened, we could move it up our priority list,” Nuttall said. This adaptability is essential to ensure the network remains effective and responsive to the region’s needs.

To date, approximately 35 of the 42 Wheatbelt shires have benefitted from funding through the WSFN, with many completing or beginning roadworks. While not every council has roads included in the network, there is collective recognition of the benefits of a connected system. This initiative aims to facilitate not only the transportation of agricultural products like grain and livestock but also to enhance accessibility for the wider community.

Nuttall pointed out that Western Australia’s extensive road network means that it is impossible to fund every single kilometre. “At the moment, local governments are completing a few kilometres of roadworks here, and a few kilometres there. We are about building a route that connects everyone up, ensuring that money is spent more effectively,” he said.

The roads constructed through the WSFN are designed to meet specific standards, ensuring a minimum lifespan of 40 years. They feature an 8-metre wide seal built on a 10-metre pavement and include line markings. Typically, rural roads with low traffic volumes do not receive line markings, but the WSFN has secured an exemption, making this a standard feature on all routes. Nuttall noted, “Most crashes in the Wheatbelt are single-vehicle run-off incidents, so an edge line is a huge factor in preventing that.”

The WSFN functions as a rolling program, allowing local governments to plan projects with the assurance of secured funding. Currently, as funding is nearly exhausted, no further projects can be initiated. Nuttall expressed concern, stating, “It would be a huge loss to the Wheatbelt if funding wasn’t secured in next year’s budget.” He acknowledged the efforts of local governments in creating wide, safe roads and emphasized the regional economic benefits, with funds remaining within the area by utilizing local contractors and Indigenous bodies wherever possible.

As the deadline for funding approaches, the future of the WSFN hangs in the balance, with numerous stakeholders advocating for the necessary support to ensure that the progress made is not lost.