High personal income tax rates are encouraging middle-to-high-income earners in Australia to engage in negative gearing, according to new research from the Australian National University’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute. The findings challenge the narrative promoted by the Greens, which suggests that wealthy landlords exploit tax breaks to dominate the housing market and make homeownership unattainable for younger Australians. Instead, the evidence suggests that it is high income tax rates that drive individuals to invest in property as a means of reducing their tax liabilities.

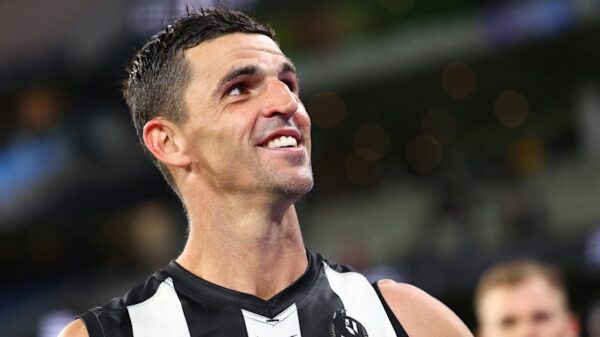

The research, conducted by former Reserve Bank of Australia economist Christian Gillitzer, reveals a direct link between marginal income tax rates and the likelihood of property investment. Gillitzer, who now lectures at the University of Sydney, found that reductions in marginal tax rates significantly decrease the incidence of negative gearing among taxpayers. His analysis focused on taxpayer data during the period from 2006 to 2011, when substantial cuts to personal income tax were implemented by both the outgoing Howard Coalition government and the incoming Rudd Labor government.

Gillitzer’s findings indicate that a decline in the marginal tax rate from 45 percent to 37 percent—achieved by raising the income threshold for the top rate from $95,000 to $180,000—led to a four percentage point drop in the likelihood of taxpayers reporting an investment property with a negative net rental position. He notes, “Ownership of debt-financed rental properties in Australia is concentrated among top earners and significantly decreases when marginal income tax rates fall.”

The implications of this research extend beyond mere academic interest. For instance, an individual earning $300,000 annually faces a tax burden of approximately $110,000 after accounting for various tax-related payments. With limited avenues for tax reduction, negatively gearing an investment property becomes a viable option for high-income earners seeking to lower their tax bills. In Australia, the unique tax treatment allows net rental losses to be fully deducted against labour income, providing a substantial incentive to invest in property.

Gillitzer’s study demonstrates that high-income earners are particularly motivated to leverage property investments due to the tax benefits associated with negative gearing. By doing so, they can shift income from the higher taxed labour income to the more favourable capital gains tax regime, which offers discounts of up to 50 percent and defers tax liabilities until the property is sold.

The political landscape surrounding these findings is complex. In early 2024, Treasurer Jim Chalmers tasked Treasury with reviewing negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount. The Greens have expressed strong opposition to these tax concessions, arguing they contribute to inflated housing prices. Yet, as various studies indicate, the combination of negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount has had a relatively modest impact on home prices, estimated at an increase of just 0.5 percent to 4.5 percent.

Despite the political rhetoric, Treasury has indicated that limiting these tax breaks for property investors may not enhance housing supply, a sentiment echoed by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Reducing tax incentives could potentially lower home prices marginally while simultaneously increasing rent, as the diminished after-tax returns for investors may deter them from developing new properties.

The debate over property tax breaks raises questions about the broader tax system in Australia. Former senior Treasury official Geoff Francis cautions that Gillitzer’s paper could be misinterpreted as a call for restricting negative gearing rather than advocating for a more equitable income tax structure. Prominent figures, including former Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating, have argued that income tax rates exceeding 39 percent are excessive.

Chalmers’ modifications to tax rates, aimed at assisting lower earners, included reintroducing a 37 percent tax rate for those earning between $135,000 and $190,000, while lowering the entry point for the top 45 percent bracket. Critics argue that these changes further incentivize leveraged property investment.

In light of these findings, a comprehensive approach to tax reform may be necessary. Experts suggest that separating labour income from non-labour income—taxing wages at progressive rates while applying a flat rate to investment income—could create a more balanced taxation system. Such reforms might not only alleviate pressure on high-income earners but also enhance government revenue capabilities, allowing for reductions in marginal rates for labour income.

As the debate continues, it becomes increasingly clear that addressing high personal income tax rates might be a key component in reforming the property investment landscape in Australia.