A coroner in New South Wales has called for urgent reforms to prison communication systems following the tragic death of a young Aboriginal man, which prevented his family from being present during his final moments. The case of Lathan Brown, a 28-year-old Kamilaroi and Barkindji man, highlights significant failures in communication that left his loved ones unaware of his critical condition until it was too late.

The inquest revealed that Lathan Brown died on January 6, 2024, at Orange Hospital, after being found unresponsive in his cell at Wellington Correctional Centre. Despite having no known medical issues, he suffered a cardiac arrhythmia, a condition that ultimately claimed his life. The inquest, held in Dubbo, emphasized the distressing impact of communication failures between Corrective Services NSW and Mr. Brown’s family, which left them unable to say goodbye.

Coroner Stuart Devine concluded that Lathan’s death was unexpected and could not have been prevented. However, he criticized the lack of timely updates provided to the family, which he described as “tragic.” The coroner urged Corrective Services NSW to implement more effective communication protocols for informing families of critical health situations involving loved ones in custody.

On the day of his death, a cellmate discovered Lathan unresponsive after hearing him cough. Emergency services were called, and he was transported to Wellington Hospital, where his pulse was briefly restored. Unfortunately, he remained unconscious and unable to breathe on his own. While Corrective Services contacted Lathan’s grandmother, who was listed as his emergency contact, they provided limited information, only describing his condition as “dire.”

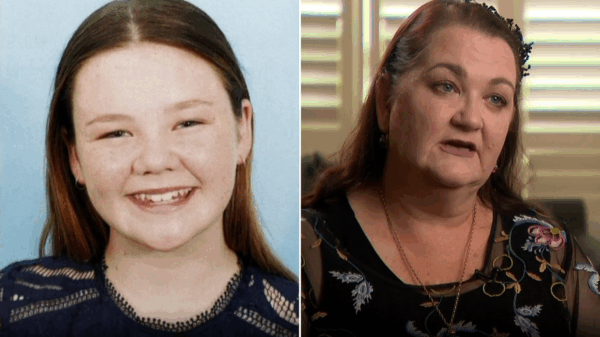

In a heartbreaking account, Lathan’s father, Michael Brown, shared his anguish over the missed opportunity to say goodbye. After receiving word that his son was being transferred to Dubbo Hospital, he drove nearly two hours, only to learn that Lathan was still at Wellington. Mr. Brown subsequently drove to Wellington Hospital, where he was denied access due to “security reasons.” He arrived at Orange Hospital just minutes after medical staff decided to withdraw life support.

“The heartbreak of lack of communication on that night, not getting updates on his condition and not being told of his whereabouts has resulted in endless pain,” Michael Brown expressed during the inquest.

Lathan Brown’s story is part of a larger narrative concerning Indigenous deaths in custody in Australia. Since the 1991 Royal Commission into Indigenous Deaths in Custody, over 600 Indigenous people have died while incarcerated, raising significant concerns among First Nations families and communities about systemic issues within the justice system.

The inquest also shed light on Lathan’s background. He grew up in Weilmoringle and Bourke and was remembered by family and friends as the “life of the party” and a respectful individual proud of his heritage. His criminal history primarily consisted of minor offences related to drug use following the death of his mother.

Legal representatives, including Tia Caldwell from the Aboriginal Legal Service, have called for immediate action to improve communication processes within the prison system. “Aboriginal people are imprisoned at almost 11 times the rate of non-Indigenous people in NSW,” Caldwell stated. She highlighted the prolonged suffering of families like the Browns, who are left in despair over the loss of their loved ones without the chance for a final farewell.

The coroner’s recommendations, which include revising communication protocols and improving the intercom systems used for distress calls within prisons, aim to protect families from experiencing similar heartbreak in the future. The call for reform underscores the urgency of addressing systemic issues that continue to affect the lives of Indigenous Australians in custody.