Researchers from the University of New South Wales have identified 21 new per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly referred to as “forever chemicals,” in Sydney’s tap water. Among these findings is a chemical that has been detected in drinking water for the first time globally. The research involved sampling tap water from four catchment sites across Sydney, including Ryde, Potts Hill, Prospect, and North Richmond.

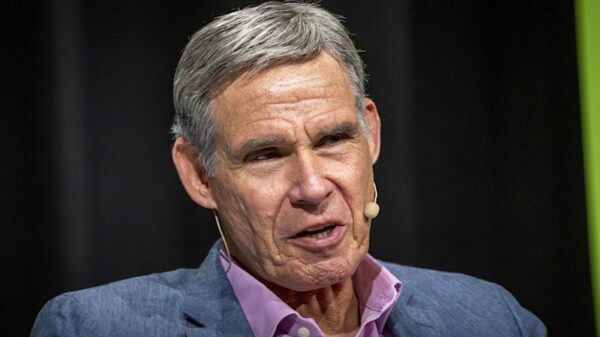

Professor Alex Donald, the lead author of the study, indicated that a total of 31 PFAS chemicals were detected. He expressed surprise at the discovery, stating, “We knew we would find more than were known, but we actually found 21 that hadn’t been reported previously in Australian drinking water.”

New Testing Methods Reveal Chemical Presence

The detection of these chemicals is attributed to advancements in testing methods that allow researchers to identify low concentrations of PFAS. Professor Donald reassured the public, emphasizing that the levels of these substances are very low, equating to “one drop of water in up to 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.” He noted that these findings remain within the safe limits established by Australian drinking water guidelines, which specifically regulate four PFAS chemicals.

Despite this, the discovery highlights the necessity for broader monitoring of water quality. Professor Donald noted that one of the newly identified PFAS chemicals has not been previously reported in any drinking water supply worldwide. “It has been picked up in various consumer products like food packaging and somehow that must have made it into the waterway, but we don’t know the origin of it,” he said.

Health Implications and Regulatory Standards

In light of these findings, comparisons were drawn to the standards set by the US Environmental Protection Agency, which considers there to be no safe level of PFAS in drinking water due to associated health risks. In contrast, the Australian government guidelines affirm a safe level of exposure. Professor Donald remarked, “Sydney’s water meets current Australian standards, but when considering health benchmarks used in other countries, some samples were near or above safety limits.”

Despite his concerns, he maintains his trust in the local water supply, stating, “I still drink the tap water, and the experts are saying it’s safe, but I think it does give you pause about just what is in there. I would like to see more research about detecting chemicals and seeing how prevalent it is.”

This research coincides with findings from an expert advisory panel established by New South Wales Health. The panel concluded that, based on extensive research, the health effects of PFAS appear to be minimal. The report adds that there is currently “no clinical benefit for an individual to have a blood test for PFAS” and cautions that “clinical interventions that reduce blood PFAS are of uncertain benefit and may cause harm.”

The study underscores the ongoing concern regarding water quality and the implications of chemical contamination, reinforcing the urgent need for continued research and monitoring.