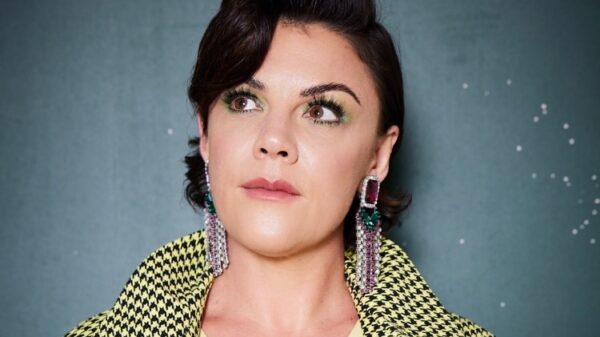

The Melbourne Theatre Company has unveiled a remarkable production of Daphne Du Maurier’s classic novel, Rebecca, directed by Anne-Louise Sarks. This adaptation breathes new life into the beloved story, captivating audiences with its stunning visuals and powerful performances. Central to the production is Nikki Shiels, who portrays the unnamed protagonist dreaming of Manderley, a grand estate that embodies both her aspirations and fears.

Shiels delivers a performance that combines authority with emotional depth, reminiscent of her role as Blanche in last year’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire. Her interpretation aligns closely with the essence of Du Maurier’s text, which was previously adapted into a film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1940. In that film, Joan Fontaine made her screen debut as the heroine, while Laurence Olivier portrayed the haunted Max de Winter, and Dame Judith Anderson left an indelible mark as the menacing housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers.

Sarks’ direction is marked by a conscious boldness, creating a visually striking atmosphere. The set, designed by Marg Horwell, features an impressive egg-shaped mirror that enhances the intimacy of the stage, reflecting the characters’ inner turmoil. This innovative design choice adds a layer of depth, transforming the performance into a visually dynamic experience.

In terms of costume design, Shiels initially appears in a modest skirt, which paradoxically evokes both innocence and sensuality. As the narrative unfolds, her character mirrors the vibrant red of Rebecca’s silks, embodying the deceased woman’s complexity and allure. The production emphasizes the feminine essence of Du Maurier’s narrative, particularly through Pamela Rabe, who not only portrays Rebecca’s ghost but also plays multiple roles, including Mrs. Van Hopper and Beatrice. Rabe’s performance is formidable, showcasing the character’s intensity and desperation.

While the production excels in many aspects, it does not come without its flaws. Stephen Phillips’ portrayal of Max de Winter lacks the captivating charisma that Olivier brought to the role. Similarly, Toby Truslove struggles to embody the charm of the character originally portrayed by George Sanders. Rabe, although powerful, does not fully capture the haunting nihilism of Anderson’s iconic performance.

Despite these shortcomings, the adaptation maintains a dream-like quality, effectively weaving together themes of love, jealousy, and identity. Sarks has approached the central elements of Du Maurier’s story with an abstract elegance, allowing for both subtlety and intensity to coexist. The production’s ability to balance these aspects ensures that it resonates with modern audiences.

As the curtain falls, the audience is left in awe, a testament to the production’s impact. The standing ovation at the conclusion underscores the emotional weight and artistic achievement of this rendition of Rebecca.

In a separate theatrical showcase, Bella Noonan is garnering attention for her stand-up performance at the Melbourne Fringe Festival. Her show, You Should See The Other Guy, features a blend of sharp humor and incisive commentary, addressing themes such as mental health and self-image. Noonan’s timing and dramatic flair have positioned her as a rising star in the comedy scene.

As the cultural landscape continues to evolve, both Rebecca and Noonan’s performance showcase the rich tapestry of talent emerging in Melbourne, reaffirming the city’s status as a hub for innovative theatre. The juxtaposition of classic adaptations and contemporary comedy highlights the diverse expressions of human experience through the performing arts.