A growing call for employers to better address workplace burnout has emerged, as employees express urgent concerns over mental health support. Many workers, including corporate manager Craig Juerchott, have shared personal experiences of burnout, highlighting a pressing need for systematic changes in workplace environments.

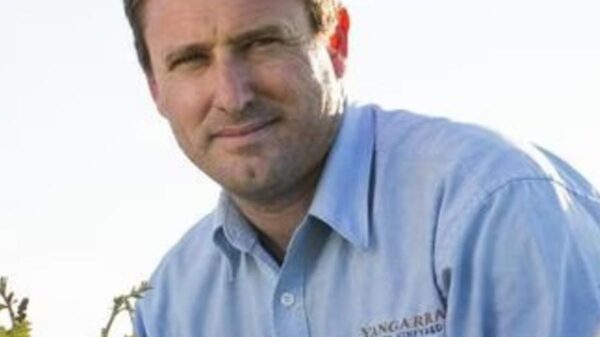

After enduring two years of intense pressure following the departure of three colleagues, Juerchott realized he was suffering from burnout. “The thing with burnout is it’s very insidious and you don’t really know how it’s affecting you until it’s too late,” he told the Australian Associated Press. The 60-hour work weeks and high expectations took a severe toll on his mental health. After leaving his job, he spent several weeks in hospital. Now, over a decade later, he prioritizes stress management.

Juerchott emphasizes that speaking out about mental health issues should not jeopardize one’s career. He believes support must be integrated into workplace systems rather than being a superficial initiative. He fears that workers still face consequences for seeking help, a sentiment echoed by 88 percent of Australians who view burnout as a critical workplace issue, according to a survey conducted by Beyond Blue involving 1,000 people.

The survey also revealed that two-thirds of respondents do not view burnout as a personal failure; instead, they attribute it to systemic issues such as excessive workloads, insufficient managerial support, and rigid working conditions. The World Health Organization has classified burnout as an “occupational phenomenon,” characterized by exhaustion, negative feelings towards one’s job, and reduced effectiveness in professional duties.

Although there are no definitive government statistics on burnout in Australia, research from Beyond Blue suggests that approximately half of all workers experience burnout within a year. Georgie Harman, CEO of Beyond Blue, stated, “What people are starting to say is we don’t want just awareness about these issues; we want workplaces to take pragmatic and practical actions.”

Creating jobs with manageable workloads and clearly defined roles is essential for addressing burnout. Harman highlights the importance of appointing confident leaders who regularly check in with their teams and listen to feedback. An effective support network, including employee assistance programs, is also crucial.

Research participants reported feelings of disconnection, with 44 percent feeling lonely at work and 18 percent fearing a lack of support from colleagues. These findings resonate with Bichen Guan, a management and organizational behaviour lecturer at La Trobe University. “Isolated people are unlikely to belong to a network from within which they can seek help,” she noted. Exhaustion can prevent individuals from forming connections that are vital for support.

While many employers are aware of burnout and offer assistance programs, Guan observed that they often take an “ad hoc” approach to helping individuals. “It’s important to provide those kinds of supports,” she added, stressing that organizations should be proactive in addressing the root causes of burnout when designing jobs and hiring leaders.

Juerchott encourages those experiencing burnout to reach out for support from friends, family, colleagues, or medical professionals. “Don’t feel like it’s going to be a gigantic mountain to climb,” he advised. “There are other people who are standing back at the base. They just don’t have that courage or strength to communicate what they’re feeling.”

The conversation around workplace burnout is shifting towards the need for comprehensive support systems that not only address symptoms but also foster a culture of openness and connection. As organizations grapple with these challenges, the emphasis on mental health in the workplace could lead to healthier, more productive environments for all employees.