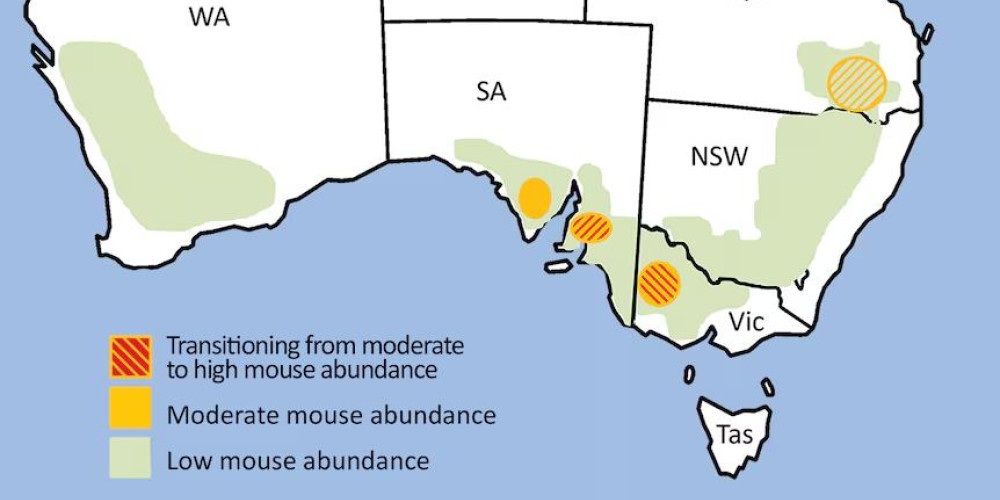

Recent warnings from the Grains Research and Development Corporation and the CSIRO indicate that conditions in the Wimmera region of Australia are ripe for a potential mouse plague in 2025. High burrow counts, with numbers reaching up to 125 per hectare in some areas, suggest that rodents are poised to breed prolifically. Historical accounts reveal that mouse outbreaks have been a recurring challenge, with significant plagues recorded in years such as 1899, 1917, 1932, and 1947.

Farmers today benefit from enhanced scientific understanding and improved communication methods that help them respond more effectively to these threats. Steve Henry, a research officer at CSIRO, noted that recent weather conditions, including significant wind, have impacted the barley crops. This leads to increased food availability on the ground, setting the stage for a potential surge in mouse populations.

“The classic sign of a problem is mice running across roads in the evenings,” Henry explained. He urged grain growers to implement preventive measures, such as sealing holes in their homes and maintaining clean surroundings to reduce contamination risks. Mice are known carriers of various diseases, including leptospirosis and gastrointestinal infections, making their management critical.

Farmers like Ryan Milgate from Minyip are drawing lessons from historical patterns to anticipate mouse population increases. “They tend to go through these cycles,” Milgate remarked. He emphasized the importance of monitoring and proactive management, stating, “Rather than trying to chase our tail and bait mice that are eating us out of house and home, we look at strategic baiting if we see numbers building up in the autumn.”

The advancements in diagnostic tools have also improved the ability to manage diseases associated with mouse infestations. Faster and more accurate testing facilitates targeted treatments. However, the challenge of antimicrobial resistance persists, underscoring the need for preventive strategies.

Milgate highlighted a technological development that has significantly aided in managing mouse populations. “Thermal rifle scopes have been a game changer,” he said. These tools allow farmers to detect mice in low visibility conditions, enhancing their ability to respond quickly to emerging problems.

Networking among farmers has also proven beneficial. “Farmers talk a lot, and they share what they’re seeing out there,” Milgate noted. This community-based information exchange helps trigger timely management actions, supported by social media platforms that facilitate the sharing of observations.

Research into long-term solutions continues at CSIRO, focusing on understanding how background food in stubbles supports mouse populations. Henry explained, “The less background food you’ve got, the better chance a mouse has of discovering bait and getting a lethal dose.”

As the Wimmera region looks ahead to the 2025 growing season, farmers are better equipped to manage the challenges posed by potential mouse plagues thanks to improved scientific insights and technological advancements. With proactive measures and community engagement, they aim to mitigate the impacts of these pests while safeguarding their crops and livelihoods.