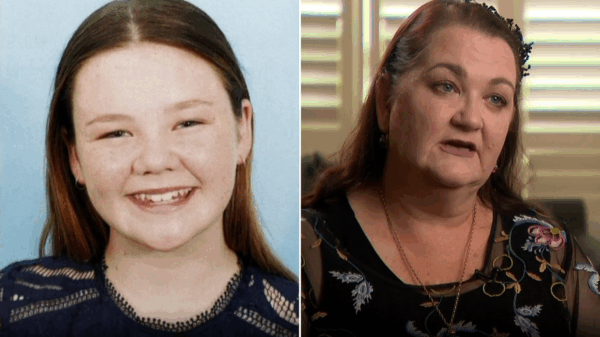

URGENT UPDATE: Dementia patients in Australia are facing significant barriers to accessing Voluntary Assisted Dying (VAD) due to stringent capacity tests, which disqualify them from choosing their end-of-life care. During a recent webinar hosted by the Older Persons Advocacy Network, Gwenda Darling, a dementia patient, expressed her frustration over being deemed “too healthy” for VAD despite her deteriorating condition.

“You can live in quite a demented state for many years… but when I have less than six months to live, I won’t have capacity and they won’t honour what I have written out,” Darling stated, highlighting the urgent need for reform.

Dr. Linda Swan, Chief Executive of Go Gentle Australia, confirmed that current VAD regulations require patients to demonstrate full decision-making capacity, effectively excluding those with dementia. This exclusion is particularly concerning as dementia has recently been labeled the deadliest condition in Australia.

The growing frustration within the community is palpable. “People are aware of the harsh realities of living with dementia and do not want that outcome for themselves,” Dr. Swan said. “Yet they feel trapped by laws that prioritize capacity over compassion.”

While VAD has been legal in Victoria for six years, awareness regarding end-of-life options remains low. Camilla Rowland, CEO of Palliative Care Australia, emphasizes that access to VAD and palliative care are not mutually exclusive. “It’s quite common for those who choose VAD to receive palliative care until the very end,” she added.

In a shocking statistic, Dr. Swan noted that nearly 30 percent of those approved for VAD ultimately opt not to end their lives, finding relief and strength simply from the approval process itself. This reflects a pressing need for better communication about the choices available to patients.

In a recent legislative battle, a proposal to limit VAD access for aged care residents in New South Wales was defeated in State Parliament. The amendment, pushed by Liberal backbench MLC Susan Carter, would have allowed facilities to block VAD access and eliminate the obligation to inform residents about their options. The bill failed by a narrow margin of 23 votes to 16 in the upper house.

As the debate continues, advocates are calling for urgent reforms to ensure that dementia patients can make informed choices about their end-of-life care. “We are a long way from answering the question of how to provide better support,” Dr. Swan concluded.

The situation remains fluid, and patients, families, and advocates are closely monitoring developments in VAD legislation. The emotional toll on those affected is immense, with many expressing a desire for more compassionate and inclusive laws that acknowledge the realities of dementia.

Stay tuned for updates as this critical issue unfolds, impacting countless lives across Australia.