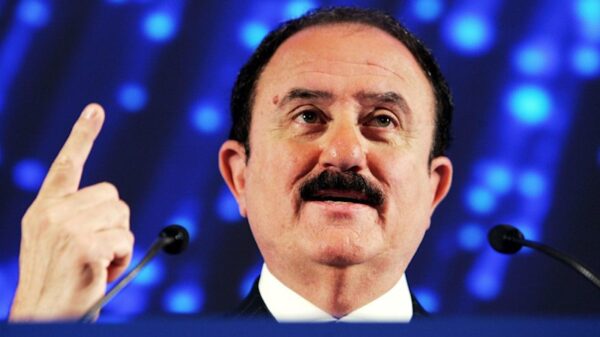

A powerful new film titled Nuremberg, directed and written by James Vanderbilt, explores the complex moral and legal dilemmas faced during the prosecution of Nazi officials following World War II. Set against the backdrop of the war’s final days, the film dives into the character of Hermann Goering, portrayed chillingly by Russell Crowe.

The narrative begins on May 7, 1945, as American soldiers encounter a Nazi vehicle in the streets of a war-torn Europe. Inside is Goering, a key figure in Adolf Hitler’s regime, whose capture raises significant questions about justice and accountability. Crowe’s portrayal of Goering is haunting, especially as he navigates the character’s duality—his politeness starkly contrasts with the horrors of his actions. Much of Crowe’s dialogue is in German, maintaining a consistent accent that adds authenticity to his performance.

As Goering becomes the highest-ranking Nazi captured alive, the film delves into the pressing issue of how to prosecute him and other surviving leaders for war crimes. Justice Robert Jackson, played by Michael Shannon, leads the prosecution at the Nuremberg Trials, where he faces the challenge of establishing legal standards for actions that had no precedent.

The American team collaborates with representatives from the United Kingdom, France, and Russia to bring the trials to fruition. To delve deeper into the psyche of these war criminals, psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, played by Rami Malek, is brought in to assess Goering and his fellow Nazis. Kelley is eager to uncover what distinguishes these individuals from the average person, sensing a potential career-defining opportunity in his research.

Supporting Kelley is American soldier Howie Triest, portrayed by Leo Woodall, who assists in facilitating conversations with the German officials. Their interactions evolve into a psychological battle, with Kelley and Goering testing each other’s limits.

While many films about World War II often depict the Americans as saviors, Nuremberg shifts focus to the psychological complexities of its characters. The film maintains engagement throughout its 150-minute runtime, largely driven by dialogue and intricate character dynamics rather than action-packed sequences.

As the trials commence, the film includes actual footage from concentration camps, providing a harrowing glimpse into the atrocities committed. This footage serves not only as a historical reminder but also contextualizes the gravity of the trials. It challenges the audience to confront the realities of the past while drawing parallels to contemporary issues.

The film subtly echoes modern sentiments, particularly when Goering expresses how a charismatic leader made him “feel German again.” This line invites reflection on the rhetoric of contemporary political figures and the social dynamics that can lead to similar ideologies gaining traction.

As Kelley attempts to sound alarms about the potential for a regime reminiscent of Nazi Germany emerging in the United States, his warnings are largely ignored. The narrative resonates with present-day societal challenges, prompting viewers to consider the importance of vigilance in safeguarding democratic principles.

In summary, Nuremberg stands as a thought-provoking exploration of one of history’s darkest chapters, delivered through compelling performances and a nuanced script. Crowe’s chilling embodiment of Goering, coupled with the film’s critical examination of justice, ensures that its themes remain relevant, echoing the necessity for accountability in any era.