An international research team, including scientists from Cornell University, has identified critical factors that contributed to the unusual behavior of the 2011 earthquake in northeastern Japan. This earthquake led to significant geological upheaval, lifting the seafloor and generating a tsunami that devastated coastal communities, including the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

The findings were published on December 18, 2023, in the journal Science. Researchers focused on the Japan Trench, where one tectonic plate descends beneath another. They discovered that the fault zone narrows into a thin, clay-rich layer lying just beneath the seafloor. This weak layer was instrumental in enabling the 2011 “megathrust” earthquake to rupture all the way to the trench, resulting in a shallow slip of between 50 to 70 meters, which displaced substantial portions of the seafloor.

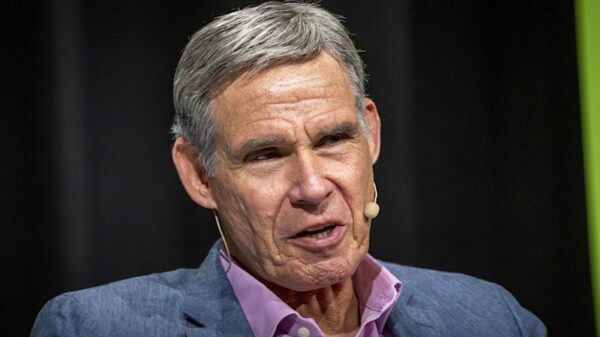

Patrick Fulton, an associate professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at Cornell Engineering, served as a co-chief scientist for the International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 405, known as JTRACK. Fulton remarked, “This work helps explain why the 2011 earthquake behaved so differently from what many of our models predicted.” He emphasized the importance of understanding the fault zone’s construction in predicting where seismic activity may concentrate and assessing tsunami risks.

In typical subduction zone earthquakes, the rupture begins deep within the fault, and the slip diminishes as it approaches the surface. Contrary to this common pattern, the 2011 earthquake exhibited increasing slip as it neared the seafloor, a phenomenon that has puzzled geoscientists for over a decade.

The JTRACK expedition, conducted in 2024, utilized a deep-sea drilling vessel to penetrate the fault and analyze sediment on the Pacific Plate. The team successfully achieved a drill-pipe length of 7,906 meters beneath the ocean surface, a feat recognized by Guinness World Records as the deepest scientific ocean drilling ever performed. Fulton highlighted the collaboration between the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, industry partners, and the international scientific community as crucial to the expedition’s success.

The study builds on previous research conducted in the region shortly after the earthquake, which initially identified the weak characteristics of the shallow plate boundary fault. Fulton, who also participated in the earlier Japan Trench Fast Drilling Project, noted that the JTRACK results offer a more comprehensive understanding of the shallow fault zone and the sediment layers involved.

During the drilling operation, scientists retrieved sediment samples that revealed a 30-meter-thick layer of pelagic clay. This soft and slippery material, formed from microscopic particles over millions of years, functions as a natural “tear line.” It concentrates the rupture along its surface, facilitating the earthquake’s propagation to the seafloor.

Fulton explained, “At the Japan Trench, the geologic layering basically predetermines where the fault will form.” He noted that this results in an extremely focused and weak surface, allowing ruptures to propagate more easily. The extensive presence of this pelagic clay layer along the Japan Trench suggests that the region may be more susceptible to shallow-slip earthquakes than previously thought.

The ultimate aim of this research is to translate detailed knowledge of fault zones into improved assessments of earthquake and tsunami hazards for coastal communities worldwide. In conjunction with the study’s publication, a 30-minute documentary has been released, showcasing the expedition’s journey. The film chronicles Fulton and his team through 105 days at sea, detailing their planning, drilling, and core sample recovery processes.

Additional data from the JTRACK expedition is anticipated to become publicly available through the International Ocean Discovery Program, further contributing to the understanding of seismic hazards globally.