In a surprising revelation, art historians are exploring the possibility that renowned artist Leonardo da Vinci may have created a nude version of his iconic painting, the Mona Lisa. Recent investigations into historical documents and artworks suggest that this centuries-old mystery could hold significant implications for understanding da Vinci’s artistic legacy.

Long queues at the Louvre Museum have become a familiar sight, attracting visitors from around the globe eager to catch a glimpse of the famed portrait. On a rainy morning, tourists patiently wait, captivated by the allure of the enigmatic woman depicted in the painting. Yet, the idea of a nude Mona Lisa raises intriguing questions about its potential impact on art and society.

Evidence of a nude version of the Mona Lisa dates back to 18th-century Britain. An engraving published by John Boydell showcased a nude interpretation of the painting, which was popular among the libertine society of the time. This version, known as “Joconda,” depicted the woman without clothing from the waist up, further fueling curiosity surrounding the original artwork. The engraving included a caption attributing it to Leonardo da Vinci, stating it was a reproduction of the painting displayed at Houghton Hall.

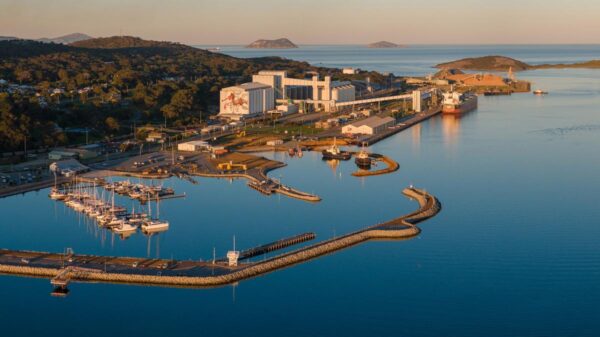

Houghton Hall, once the residence of Sir Robert Walpole, was famous for its extensive collection of art. The painting allegedly inspired by the Mona Lisa was thought to be an actual work of da Vinci. According to the catalog compiled by Walpole’s son Horace, this version was associated with the historical figure of Lisa del Giocondo, believed to be the muse behind the original painting.

An intriguing document from Heidelberg University indicates that da Vinci began the Mona Lisa in Florence around 1503. During his later years in France, he presented the painting to notable visitors, including Cardinal Luigi of Aragon. However, evidence suggests that Leonardo may have been withholding key information about the painting’s origins and purpose.

A significant lead arises from Leonardo’s time in Rome, where he worked under the patronage of Giuliano de’ Medici. Historians speculate that da Vinci might have created a nude version for the nobleman, given the intimate nature of their relationship. A preparatory drawing known as a “cartoon,” dated between 1514 and 1516, found in a chateau near Paris, portrays a naked model resembling the Mona Lisa. The Louvre confirmed in 2017 that this drawing bears characteristics consistent with da Vinci’s style.

This connection between the nude cartoon and the Mona Lisa raises questions about Leonardo’s creative process. The positioning of the figure’s arms and hands aligns closely with the iconic painting, suggesting that the artist might have explored different representations of his subject.

Moreover, the influence of Raphael, a prominent figure of the time, cannot be overlooked. His work, La Fornarina, features a young woman in a pose reminiscent of the Mona Lisa. The similarities in composition and style suggest that Raphael may have drawn inspiration from da Vinci’s nude interpretation, further intertwining their artistic legacies.

As research continues, art historians are left with compelling questions: Did Leonardo da Vinci indeed paint a nude version of the Mona Lisa? If so, what does this reveal about his artistic intentions and the cultural context of the Renaissance? The narrative surrounding the naked Mona Lisa adds a layer of complexity to the understanding of this masterwork.

Leonardo’s remarkable ability to blend realism with idealism invites deeper analysis of his motivations. If the nude version was an extension of his creative exploration, it underlines the duality of his artistic vision—capturing both the beauty of the human form and the intricacies of human emotion.

The prospect of a nude Mona Lisa challenges contemporary perceptions of the painting and the artist. As this investigation unfolds, it highlights the enduring intrigue of Leonardo da Vinci and the timeless nature of his work, compelling audiences to reconsider the significance of one of history’s most celebrated paintings. Such revelations remind us that great art can provoke thought and inspire dialogue across generations.